Online collaborative storytelling is an idea that people seem to get excited about in waves. At the peak of a given wave, designers and observers rightly express confidence that wholly new and powerful kinds of storytelling are just around the corner (or, indeed, are already happening all around us). Given the affordances of the Web and social media, this enthusiasm is perfectly justifiable. But in the troughs between these waves of excitement, cautionary voices express the very real difficulties of mobilizing, structuring, and sustaining collective storytelling practices. These voices question the ability of user-generated content to create the kinds of focused and meaningful narrative figures that can be found in more traditional storytelling forms. And then, inevitably, something happens that throws this pessimism into question, and the cycle continues.

Part of the reason the energy around collaborative storytelling moves in these cycles is that we’re still in the midst of a rapid and fumbling expansion of our understanding of the scope and potential of networked transmedia production. Our anxieties about the practicalities and capabilities of collaborative storytelling are a product of our natural tendency to seek out the familiar: by looking for ways that the interplay of crowds can create the kinds of feelings and experiences we get from single-author or closed-team texts like films, novels, and plays, we can sometimes lose sight of the fundamentally new kinds of narrative structures and experiences made possible by social media and pervasive computing.

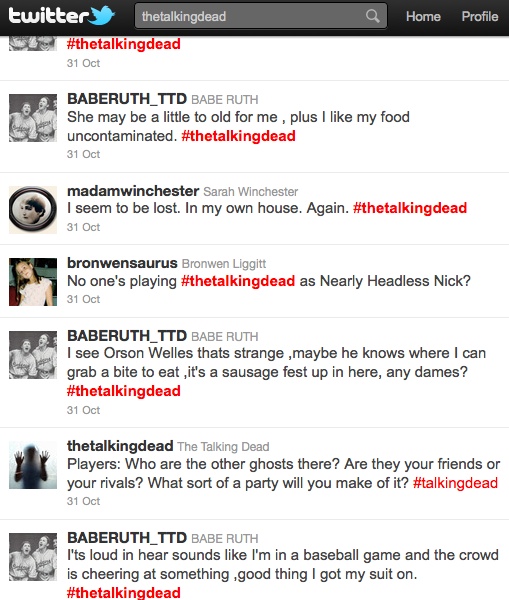

Two recent collaborative storytelling events illustrate how a shift in the way we conceive of stories being produced and consumed can open up a world of new possibilities. The first of these is the latest in Jay Bushman’s Halloween-themed massively collaborative Twitter experiments, “The Talking Dead.” Bushman describes the project as an “interactive story event where you play a ghost that haunts social networks.” Players are invited to create fake Twitter accounts for dead people — usually celebrities, though Jay is careful to say that any kind of dead person will do — and then post status updates from beyond the grave. Andrea Phillips has written some brilliant coverage and analysis of the project, so I won’t delve much further into a description here.

What I find important about “The Talking Dead” and Jay’s other collaborative Twitter dramas is that they tackle the high-bar-to-entry problem that plagues so many collaborative storytelling ventures by letting go of the desire for central authorial control. True, Jay sets a very specific tone and frames the participation in a variety of ways in order to productively constrain the creativity of the participants; but he does not (indeed, largely can not) “police” the contributions: players are free to post whatever they want, and the tone and direction of the improvisation emerges through an organic push and pull. Further, all this collaboration is facilitated using free and popular web tools — Twitter for the status updates and Tumblr to aggregate and archive the content that gets created — which means that even a smallish turnout is more than worth it in terms of bang for the producers’ buck.

The second example I’d like to point out here takes the principle of emergence in collaborative storytelling a step further. In this case, the constraints for the collaboration themselves were created and iterated through a collaborative process, emerging out of a sense of outrage shared by the readers of a post submitted to Reddit and other link sharing networks. Obviously, it’s not the first time this sort of thing has happened on the interwebs, but it’s a great example of how a multimodal networked storytelling collaboration can emerge almost out of thin air:

The tale of writer Monica Gaudio hit the Web on Wednesday after she reported that her story, “A Tale of Two Tarts,” was apparently lifted and published by the print magazine Cooks Source with her byline, but without her knowledge or any compensation. After tracking down the editor at the magazine, Gaudio asked for an apology on Facebook and in the magazine, as well as a $130 donation to the Columbia School of Journalism.

Instead, she said she received a rather unexpected response from the editor, Judith Griggs, quoted in-part below:

“But honestly Monica, the Web is considered ‘public domain’ and you should be happy we just didn’t “lift” your whole article and put someone else’s name on it! It happens a lot, clearly more than you are aware of, especially on college campuses, and the workplace. If you took offense and are unhappy, I am sorry, but you as a professional should know that the article we used written by you was in very bad need of editing, and is much better now than was originally. Now it will work well for your portfolio. For that reason, I have a bit of a difficult time with your requests for monetary gain, albeit for such a fine (and very wealthy!) institution. We put some time into rewrites, you should compensate me! I never charge young writers for advice or rewriting poorly written pieces, and have many who write for me… ALWAYS for free!”

After Gaudio went live on her blog page with details of the transaction, and other blogs picked it up, it didn’t take long for the viral nature of the Internet to take hold. Cooks Source’s Facebook page, which had only around 100 “friends” beforehand, took on a whole new popularity, though probably not in the way the magazine wanted. (CNET)

A quick search of Facebook for “Cooks Source” now reveals a plethora of fictional oddities and improvisational story bits created by people for whom the story of Monica Gaudio struck a nerve. Some of the content unsettlingly straddles the line between comedy and a kind of cyberbullying; but in the mean, the tone of the improvisation is surprisingly unified: Cooks Source went too far and is now being snarked into submission via sarcastic comments posted to its Facebook page and fictional Facebook groups and pages like “But honestly Monica, the web is considered ‘public domain’.”

In contrast to “The Talking Dead,” participants in the Cooks Source intervention (for want of a better term) did not come to the activity in the spirit of “let’s pretend”; rather, their initial motivations were something like, “let’s do something about this” or “let’s punish this company for its thoughtlessness.” Storytelling and performance — across a variety of platforms and modes — was just the most natural and fitting way to achieve this objective. No one framed or guided the experience, but in the end, a miniature transmedia archive emerged, remixing the intended messaging of Cooks Source magazine [ed.: hey, shouldn’t there be an apostrophe in there?] to create a variety of satiric and comedic figures.

Neither of these examples tell stories in the manner we’re used to from our experiences with most other kinds of media artifacts — but the aggregate effect is undeniable: the spontaneous creation of a story world out of the bits and pieces of a collective improvisation.