[intro]I met Andrea Phillips at this year’s SXSW, where she delivered a smart, wide-ranging talk about the representation of women in ARGs. Andrea is a veteran ARG writer, designer, and player, and is the current chair of the IGDA ARG Special Interest Group. In this interview, Andrea discusses her creative process and the formal and technical limitations (and possibilities) of ARGs and other playful forms of transmedia storytelling:[/intro]

You’re a self-identified science fiction writer working in a very hard-to-pin-down storytelling medium. How did you end up writing and designing ARGs?

I was one of the moderators for the Cloudmakers, back in 2001. As a writer, it was like a lightning bolt falling from heaven. I went through the experience and thought, “That. I want to do THAT.” It took a few years to go anywhere, though. Finally my fellow moderators, Dan and Adrian Hon, started talking about forming the company that would later become Mind Candy. I begged them to let me help out so relentlessly that they had no choice but hire me. I’ve been in the business ever since.

One of the things that is quickly becoming an issue with game and transmedia writing is the sometimes tenuous position of the writer in the apparatus of production. How do you think being an ARG writer differs from being, say, a TV writer or a novelist?

At its best, writing for an ARG is a performing art. When you write a novel, you work in isolation; you won’t get feedback from the bulk of your readers until it’s completed. And with a TV show, production schedules mean the writing is completed sometimes months before a show airs.

With an ARG, though, you can dance with your audience. If they take a shine to a minor character, you can boost that character’s role midstream. If they’re bored with a plot thread, you can catch it early and fix it. And that kind of feedback is addictive to a writer. It can be difficult to get that kind of feedback in other media at all. But in an ARG, you’re doing something close to watching their faces as they read along, so you know when you’re succeeding and when you’re failing.

In the larger realm of production and transmedia, though, I think this causes some logistical problems. A great transmedia experience requires an agility that traditional means of production just don’t have, and the writer can be placed in a difficult position, trying to maintain the integrity of the experience while working within the framework of your production schedule.

In a recent post on this issue on your blog, you wrote that sometimes “there are so many writers working on a project that it’s hard to know whose hand [is] guiding the wheel. But these are solveable problems, and solving them would benefit us all.” What kinds of first steps do you think need to be taken to advance the cause?

The first step would be looking at the kinds of roles game writers and transmedia writers fall into right now, to see if we can find common structures. In games, there’s a lot of support for the title ‘narrative designer’ right now. That’s the person who comes up with the spine of the story, whether or not they ever write a word of player-facing copy. Maybe we need to go in that direction, and separate the narrative designer from the world designer.

And given the performative element of an ARG, maybe we need to be crediting writers alongside actors. ‘The character of Alice Liddell was performed by Ada Lovelace, and written by Marshall Thurgood.’

Shifting gears a bit, I’m curious about how you tackle the complex demands of ARG writing and design. After meeting with a client, where do you begin? What comes first for you, the formal constraints (ie, the kinds of interactions you want to produce) or the story material?

Everything I do begins with a big idea. Sometimes that’s mine, and it springs into existence fully-formed — “What if everyone wrote about waking up with superpowers?” Sometimes it’s the assignment given to me by a client. “We have XYZ requirements and assets. What do you have for us?”

From there, I do a little research and a little bit of what looks from the outside like nothing at all. Going to the gym, walking to school, cooking. The important thing is that I leave my brain unoccupied so it’s free to come up with stuff, like particles popping into existence in a vacuum. As the idea simmers in the back of my head, everything about what the project should look like becomes obvious to me. It feels very much like discovering something that was already there.

Specific story elements come last for me. Tension and pacing and structure are the first things that come to mind, and the specific plot and story elements flow out of that. It’s the opposite of the way I did things a few years ago. I used to think of story and plot detail first! I’m not sure why it’s changed, but I’m helpless to do it any other way, now.

Historically, most ARGs have been event-driven time-released stories with beginnings, middles, and ends. One of the nice things about this narrative structure is that it allows writers to plan (and re-plan, as conditions on the ground shift) their stories in much the same way that they do in more traditional forms: that is, via character arcs, acts, orchestrated patterns of conflict, and so on. However, these kinds of ARGs are usually not replayable, and many people — for many reasons — feel that this is an area where the form could stand to experiment a little bit. What are your thoughts on this?

I agree that we need to experiment more. But the good news is that the experimenting is going on now.

Not to toot my own horn, but one of the things my project Routes did was creating a weekly webisode from the events in the ARG, so you could interact with the live experience while it played out, but there is also an artifact of the experience that gives the project a long tail it wouldn’t have otherwise. In the metaphor of the ARG as a live concert, that’s creating a recording you can listen to at any time. You won’t be able to do all of the same things — you won’t be able to throw your underwear up on stage or smell the guy in front of you — but you’ll get some sense of what it was like to have been there. I think this technique could definitely move into wider use.

And there are a number of entirely replayable experiences, too: Smokescreen, the Cathy’s Book series, etc. The downside of this is that you lose some wonder, some discovery, a ton of reactivity, and the camaraderie of a single community playing along together. It transforms into a different kind of experience.

So can a system for storytelling — that is, a set of story-world parameters and rules of engagement — be considered a kind of fiction? If so, how does this change our understanding of what a writer is?

Oh, it absolutely can. I’d consider My Super First Day to be a set of very loose story-world parameters that I’ve set, and I consider it a work of fiction. It doesn’t make me a writer, though; I only get to be a writer if I also participate. But I’m indisputably the creator.

You may also be familiar with Ghyll and The Song of the Sorcelator, both arguably just frameworks for writer-participants to play around with. This is one of the things I keep playing around with in my personal work, actually; where is the line between a creator and a participant, and how can you blur it in a way that will be rewarding to everybody?

As time goes on, I think the boundary will become ever more nebulous. We’re already seeing major entertainment franchises take a kinder, gentler stand on fanfiction and fanart. That’s the first step in building collaborative culture. The secret, of course, is that once you’ve given your audience official permission to collaborate with you in any meaningful sense, they’re yours forever, hook, line, and sinker.

Where do you see all this going in the next five years? And what’s next for you?

Five years is an incredibly long time. Five years ago, there was no such thing as Facebook or Twitter, and when you walked into a digital agency and said ‘interactive’ they thought you were talking about banner ads and SEO. I think in five years, the entire entertainment landscape is going to look so profoundly different that anything I have to say on it is worthless.

As for me, I have a couple of things cooking right now. I try to do enough professional projects to keep the rent paid, and enough personal projects that I feel I’m always pushing my own limits. But my personal projects are largely microscopic in scale and experimental to the point of self-indulgence. I’m thinking about trying to do a bigger, more ambitious experimental personal project toward the end of the year, and possibly funding through Kickstarter or some such thing. I’m not sure what it would look like, but I feel like it would be a shame not to try. The creative life is all about taking risks.

Thanks, Andrea!

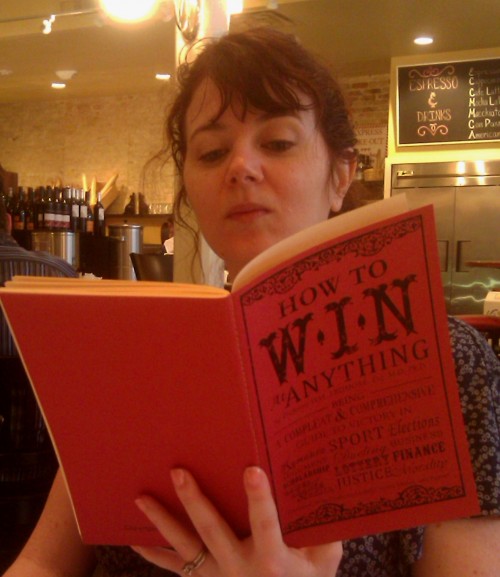

UPDATE: get your own copy of “How to Win at Anything” (pictured above) here